What is a CDN...?

Content delivery networks (CDN) are the transparent backbone of the Internet in charge of content delivery. Whether we know it or not, every one of us interacts with CDNs on a daily basis; when reading articles on news sites, shopping online, watching YouTube videos or perusing social media feeds.

No matter what you do, or what type of content you consume, chances are that you’ll find CDNs behind every character of text, every image pixel and every movie frame that gets delivered to your PC and mobile browser.

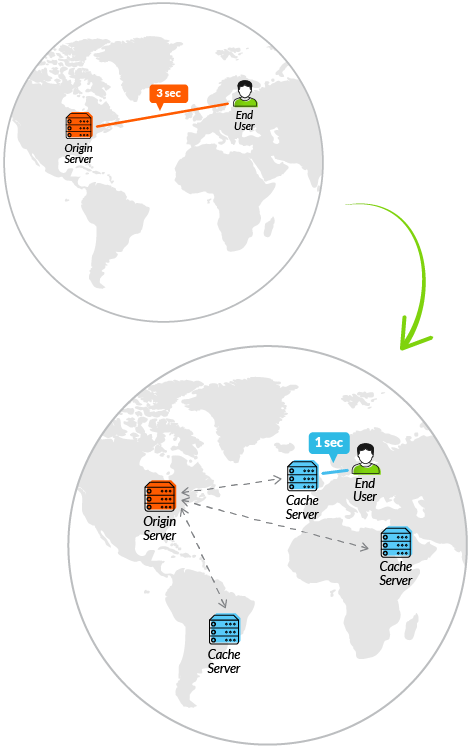

To understand why CDNs are so widely used, you first need to recognize the issue they’re designed to solve. Known as latency, it’s the annoying delay that occurs from the moment you request to load a web page to the moment its content actually appears onscreen.

That delay interval is affected by a number of factors, many being specific to a given web page. In all cases however, the delay duration is impacted by the physical distance between you and that website’s hosting server. A CDN’s mission is to virtually shorten that physical distance, the goal being to improve site rendering speed and performance.

How a CDN Works...?

To minimize the distance between the visitors and your website’s server, a CDN stores a cached version of its content in multiple geographical locations (a.k.a., points of presence, or PoPs). Each PoP contains a number of caching servers responsible for content delivery to visitors within its proximity.

In essence, CDN puts your content in many places at once, providing superior coverage to your users. For example, when someone in London accesses your US-hosted website, it is done through a local UK PoP. This is much quicker than having the visitor’s requests, and your responses, travel the full width of the Atlantic and back.

This is how a CDN works in a nutshell. Of course, as we thought we needed an entire guide to explain the inner workings of content delivery networks, the rabbit hole goes deeper.

Who Uses A CDN...?

Pretty much everyone. Today, over half of all traffic is already being served by CDNs. Those numbers are rapidly trending upward with every passing year. The reality is that if any part of your business is online, there are few reasons not to use a CDN especially when so many offer their services free of charge.

Yet even as a free service, CDNs aren't for everyone. Specifically, if you are running a strictly located website, with the vast majority of your users located in the same region as your hosting,

having a CDN yields little benefit. In this scenario, using a CDN can actually worsen your website’s

performance by introducing another unessential connection point between the visitor and an already

nearby server.

Still, most websites tend to operate on a larger scale, making CDN usage a popular choice in the

following sectors:

1. Advertising

2. Mobile

3. Media and Entertainment

4. Health Care

5. Online Gaming

6. Higher Education

7. Government

CDN Building Blocks

PoPs

(Points of Presence)

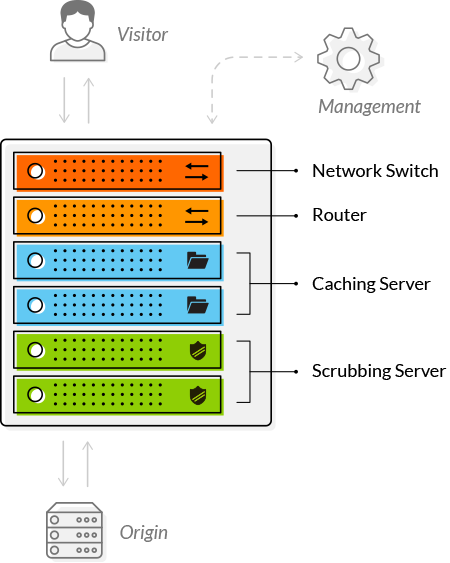

CDN PoPs (Points of Presence) are strategically located data centers responsible for communicating with users in their geographic vicinity. Their main function is to reduce round trip time by bringing the content closer to the website’s visitor. Each CDN PoP typically contains numerous caching servers.

Caching Servers

Caching servers are responsible for the storage and delivery of cached files. Their main function is to accelerate website load times and reduce bandwidth consumption. Each CDN caching server typically holds multiple storage drives and high amounts of RAM resources.

SSD/HDD + RAM

Inside CDN caching servers, cached files are stored on solid-state and hard-disk drives (SSD and HDD) or in random-access memory (RAM), with the more commonly-used files hosted on the more speedy mediums. Being the fastest of the three, RAM is typically used to store the most frequently-accessed items.

Start Using A CDN

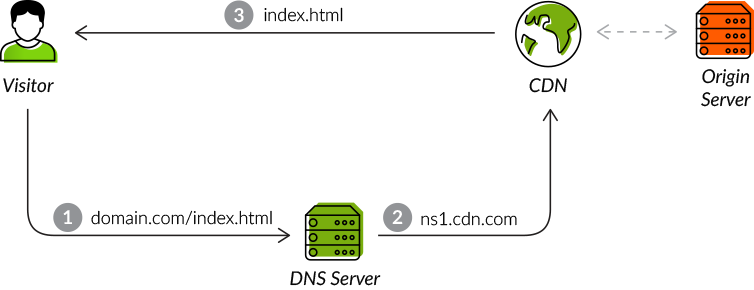

For a CDN to work, it needs to be the default inbound gateway for all incoming traffic. To make

this happen, you’ll need to modify your root domain DNS configurations (e.g., domain.com) and

those of your subdomains (e.g., www.domain.com, img.domain.com).

For your root domain, you’ll change its A record to point to one of the CDN’s IP ranges. For each subdomain, modify its CNAME record to point to a CDN-provided subdomain address (e.g.,ns1.cdn. com). In both cases, this results in the DNS routing all visitors to your CDN instead of being directed to your original server.

If any of this sounds confusing, don’t worry. Today’s CDN vendors offer step-by-step instructions to get you through the activation phase. Additionally, they provide assistance via their support team. The entire process comes down to a few copy and pastes, and usually takes around five minutes.

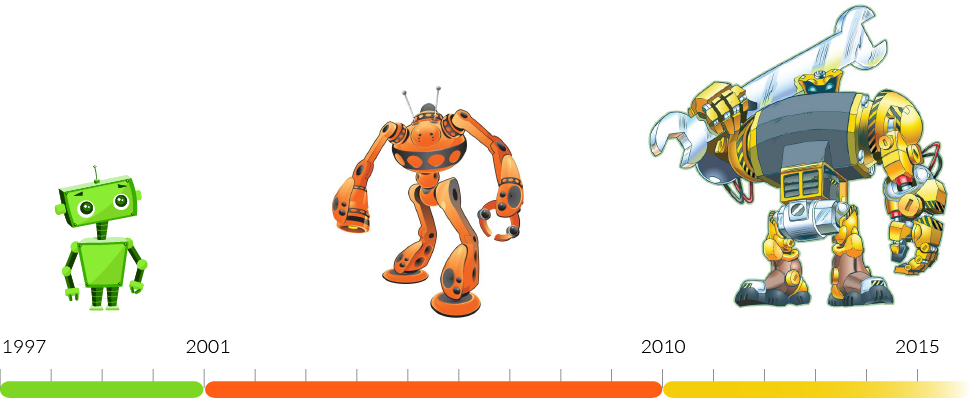

The Evolution of CDNs

Commercial CDNs have been around since the ’90s. Like any other decades-old technology, they went through several evolutionary stages before becoming the robust application delivery platform they are today.

The path of CDN development was shaped by market forces, including new trends in content consumption and vast connectivity advancements. The latter has been enabled by fiber optics and other new communication technologies.

Overall, CDN evolution can be segmented into three generations, each one introducing new capabilities, technologies and concepts to its network architecture. Working in parallel, each generation saw the pricing of CDN services trend down, marking its transformation into a mass-market technology.

The Evolution of CDNs

1st Gen 2nd Gen 3rd Gen

Static CDN Dynamic CDN Multi-Purpose CDN

Reverse Proxy Living on the Edge

Content delivery networks employ reverse proxy technology. Topology wise, this means CDNs are deployed in front of your backend server(s). This position, on the edge of your network perimeter, offers several key advantages beyond a CDN’s innate ability to accelerate content delivery.

Today, the reverse proxy topology is being leveraged by multi-purpose CDNs to provide the following types of solutions:

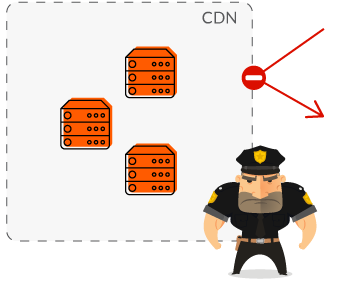

Website Security

Cyber Security is all about managing outside access to your protected perimeter, ideally blocking all threats before they can even set foot on your doorstep.

Deployed on the edge of your network, a CDN is perfectly situated to act as a virtual high-security fence and prevent attacks on your website and web application. The on-edge position also makes a CDN ideal for blocking DDoS floods, which need to be mitigated outside of your core network infrastructure.

Load Balancing

Load balancing is all about having a “traffic guard” positioned in front of your servers, alternating the flow of incoming requests in such a way that traffic jams are avoided.

Clearly, a CDN’s reverse proxy topology is ideal for this, as is the default recipient of all incoming traffic. In addition, reverse proxy topology also provides a CDN with enhanced visibility into traffic flow. This lets it accurately gauge the amount of pending requests on each of the backend servers, thereby enabling more effective load distribution.

CDN Infrastructure

The choice of infrastructure architecture is critical to shaping a CDN’s product identity while also defining the value of its offering. The basic building blocks of CDN infrastructures are PoPs (points of presence)—regional data centers responsible for communicating with users in their proximity.

Using regional content distribution centers cuts down on round-trip time (RTT), making your website faster and more responsive for all visitors, regardless of their geolocation.

Typically, each PoP holds multiple servers and routers responsible for caching, connection optimization and other content delivery features. For CDNs providing security solutions, PoPs also hold DDoS scrubbing servers and machines responsible for other security-related functions.

Remember, a CDN’s job is to enhance your regular hosting by reducing bandwidth consumption, minimizing latency and providing the scalability needed to handle abnormal traffic loads. These tasks can only be achieved by a robust network architecture—one that turns your CDN into a dedicated fast lane on the information superhighway.

Round-Trip Time

Round-trip time (RTT) is the number of milliseconds (ms) it takes for a browser to send a request and receive a response back from a server. RTT is not influenced by file size or the speed of your Internet connection. Instead, it’s affected by:

Physical Number of Amount of Transmission

Distances Intermediate Nodes Traffic Mediums

RTT is where the battle for speed is typically won and lost, since no rendering in the user’s browser can begin before the initial outgoing request for the HTML file is returned.

The Four Pillars of CDN Design

Performance

One of a CDN’s main missions is to minimize latency. From an architectural standpoint, this means having to build for optimal connectivity, where PoPs are located at major networking hub intersections where data travels.

Physical facilities are another important consideration. As a rule, you always want your PoP to be in a premium data center where backbone providers peer with each other and your CDN provider has established peering agreements with other CDNs and major carriers. Such agreements enable CDNs to significantly reduce round-trip times and improve bandwidth utilization.

Reliability

CDN infrastructure scale makes a glitch-free system a statistical improbability. However, this same scale can help ensure record resilience and high-availability, enabling CDN providers to commit to 99.9% and 99.999% service level agreements (SLAs).

As a rule, commercial CDNs adopt a “no single point of failure” approach, both by carefully phasing maintenance cycles and by integrating additional hardware and software redundancy. Many also manage internal failover and disaster recovery systems that auto-route traffic around downed servers. For additional redundancy, CDN providers also deal with multiple carriers and rely on dedicated out-of-band management channels that allow them to interact with servers in case of disaster.

Scalability

Built for high-speed and high-volume routing, CDNs are expected to handle any amount of traffic. CDN architecture should address these expectations by providing ample networking and processing resources on all levels—down to computing and caching resources available on each of the caching servers.

As one would expect, CDNs offering DDoS protection services have much higher scalability requirements. To address these needs, they deploy dedicated servers built for DDoS mitigation (scrubbers). These can individually handle network-sized amounts of traffic, processing tens of gigabytes each second.

Responsiveness

With a global-sized network, CDNs continually strive to improve responsiveness—measured in the amount of time it takes for network-wide configuration changes to take effect.

Keep in mind that even small configuration changes, like an order to purge a specific image from cache or the addition of an address to a blacklisted IP list, need to be communicated across all PoPs. The larger and more geographically spread out the network, the longer it takes to accomplish this.

To ensure good quality of service to customers, the CDN should be designed with quick configuration propagation in mind. This is commonly achieved with a combination consolidate.

No comments:

Post a Comment